The Mystery of the Origin of Indian Yellow

Indian yellow, the famous deep mustard yellow pigment, is known as peorī in Hindi, or gogilī, an Indianized version of the Persian term gaugil, meaning “cow-earth”.

Indians themselves traditionally used the pigment for coloring their calicoes [cotton cloths], which they used without any mordant, so that the color was washed out again when the cloth was dirty. Another early traditional use described was its use in a blend of “gogoli” with “kesar or saffron (Crocus sativus)” for Mithila painting in Bihar. It was also used as watercolor in Pahari miniatures (16th–19th century). In addition, a yellow pigment called gorocana, cited as being prepared from cows’ urine, was an ingredient of ritual items, applied as a ‘tilaka’ on the forehead, and used in Ayurveda as a healing substance — as a “cow essence”; Goracana it is still used in Tibet and is said to come from the gallstones of cattle.

Indian yellow was a pigment that was produced in India and brought to Europe via merchants in Calcutta. There is evidence of the pigment reaching England as early as the 1780s, and suggestion that it reached the Netherlands even earlier in the 17th century, through trade with the East Indies.

By European artists, Indian yellow was admired for its transparency, its beautiful pure yellow color, light powdery texture, and utility for compounding greens, orange and other colors. The pigment was popularized in Europe by Dutch painters, including Jan Vermeer, who enjoyed the unique lightfastness of this extraordinary yellow. Indian yellow became part of JMW Turner’s watercolor palette and the Scottish Colorists adopted it in oil form.

One of its most famous users was Van Gogh, who painted a luminous Indian yellow moon in his 1889 masterpiece, The Starry Night.” It has been featured in expositions, and esteemed for its beauty used in both watercolor and oil painting.

In watercolor, it was described as “resisting the sun’s rays with singular power”, but in “ordinary light and air, or even in a book or portfolio, the beauty of its colour is not lasting”. Indian Yellow owes its translucence and near fluorescence to its water-soluble structure. In its original form, it was known as a lake pigment — made from organic materials unlike colors like ultramarine and vermillion are created by crushing minerals.

A description in 1905 from Alexander Eibner, a German chemist and painting technologist, states “the pure pigment has an incomparably beautiful, deep and luminescent gold yellow in shade which is achieved with no other pigment”. Eibner also published the results of light aging studies — concluding that Indian yellow was a stable watercolor pigment, which could withstand daily sunlight for two years without observable color or intensity alterations.

The first published reference to Indian yellow as a pigment was in 1805 in M. Gartside’s essay “An Essay on Light and Shade” — mentioned without a description or any other information. In ‘The Art of Painting in Oil and in Fresco’, J.F.L. Mérimée, in 1839, describes Indian yellow as “a brilliant yellow lake” and that “the colouring matter is extracted from a tree, or a large shrub called Memecylon tinctorium” and that had “a smell like cows’ urine”.

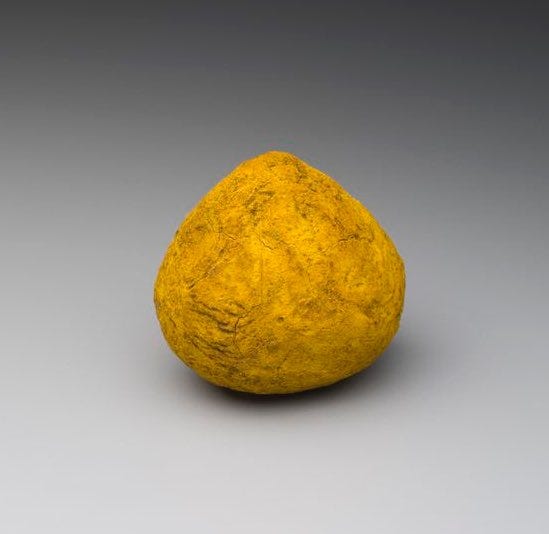

The origins and components of Indian yellow were largely unknown at the time. For years, soft yellow lumps arriving by ship in sealed packages to European docks. The dirty yellow balls would be washed and purified, and the greenish and yellow phases separated. The precise ingredients of these lumps were not known, but they had a pungent odour of ammonia and were suspected of containing camel or cow urine or ox bile.

The debate on the origin of Indian yellow was left open until 1883, when Dr. Hugo Muller wrote to Sir Joseph Hooker, a respected scientist and botanist, and director of Kew Gardens (1865–1885), for information on Indian yellow. Sir Joseph Hooker, desired to settle the debate once and for all. He assigned to the task Trailokya Nath Mukharji, a high ranking official in the Department of Revenue and Agriculture of the Government of India, who also served as curator for the Indian Museum, Kolkata, and was an expert on materials and resources in India. (He also published multiple book, incliuding A Handbook of Indian Products, Art-manufactures and Raw Materials).

T. N. Mukherji travelled to Monghyr (Munger) in Bihar, along the Ganges river in search of Indian yellow. There, he found a sect of gwalas (milkmen) in the suburbs of Mirzapur who were responsible for manufacturing the pigment. In his report, originally published in the Journal of the Society of Arts, 1833, and later republished in the Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), he states: “They feed the cows solely with mango leaves and water, which increases the bile pigment and imparts to the urine a bright yellow color”, and that “in no other part of the country is the manufacture of Piuri carried out”. He then goes into details about the collection and processing of the urine and hand-pressing into the Piuri ball. The cows were trained to pass urine four times a day by slightly rubbing their urinary organs, and it is collected in small earthen pots, a which were placed over a fire overnight to condense the liquid, leaving a yellow precipitate. It would then be strained through a cloth, and the sediment made into a ball and dried further, first, on a charcoal fire, and then in the sun. The Piuri is then ready for the markets. The merchants would advance money to the milkmen, and export the pigment to Calcutta and Patna, and from there it would be shipped to post-impressionist Europe. The Piuri was purchased from the milkmen by Marwari traders for 1 Rupee per pound, and once it arrived in Calcutta the price could be up to 100 to 200 Rupees. Mukharji concludes by stating firmly that he himself saw mango leaves being eaten by the cows, the urine being collected, and the manufacturing of the pigment, as well as, “the real source of this kind of Piuri is now beyond any doubt whatsoever”.

Despite this eye witness account, since it was the unconfirmed by other eyewitnesses except Mukherji, few accepted the theory and continued to debate the origin of Indian yellow. Scientists Erdmann and Stenhouse, independently performing experiments on the pigment, established its main chemical composition as euxanthic acid — though still speculative of the exact origin. The chemical structural information of euxanthic acid, the principal compound in Indian yellow, and its relevance to physiology was explored throughout the 19th century by a number of prominent chemists in Europe. But it was not until the 1950s that the mechanism of its metabolic production naturally in the body and its importance in drug metabolism was finally understood and proven. Following this discovery of the physiologic production of glucuronic acid and the metabolic process of conjugation called glucuronidation, we begin to see references to the production of the primary component of the pigment, euxanthic acid, in cows from euxanthone and glucuronic acid — confirming its composition to be a purified urinary sediment, as Mukharji’s original report stated. The high concentration of polyphenolic compounds such as those found in mangos appears to be required for the high production of euxanthic acid via glucuronidation reactions. Euxanthic acid has not been identified from any other plant, fungi or lichen source, or even in mango (Mangifera indica), including from the bark, kernels, leaves and mango fruit peels, which, however, contain a range of xanthone derivatives.

The confusion regarding its composition was due to the fact that many products were being exported from India under the East India Company and British Raj that were called Indian yellow or one of the many variations of the name “peori” in Hindi and “googol” in Persian. Many other materials too were catalogued as Indian yellow, such as Hardiwárí peori (natural Indian yellow), Vilayati peori (lead chromate), and cobalt yellow (aureloin).

The production of the pigment decline gradually starting in the 1920s, most probably due to the cruelty to animals involved in the process — since the cattle were fed an exclusive diet of mango leaves and water in order to increase the saturation of their urine, (occasionally with a little turmeric thrown in for good measure), it did not provide them with adequate nutrition and the cows were often malnourished. The toxin urushoil found in mango leaves also took a toll on the cows.

Sources:

- The story of Indian yellow — excreting a solution Rebecca Ploeger∗, Aaron Shugar; Art Conservation Department; SUNY, Buffalo State (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1296207416304277)

- “Indian Yellow” in Artists’Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, National Gallery ofArt, Washington, 1986; N.S. Baer, A. Joel, R.L. Feller, N. Indictor.

- Spotlight on: Indian Yellow, Winsor and Newton (https://www.winsornewton.com/uk/articles/colours/spotlight-on-indian-yellow)

- A History of Color: An Audio Tour of the Forbes Pigment Collection: Harvard Art Museums (https://harvardartmuseums.org/tour/a-history-of-color-an-audio-tour-of-the-forbes-pigment-collection/slide/11168)

- “Indian Yellow.” Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), vol. 1890, no. 39, 1890. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4111404.

Also By T. N Mukherjee -

Art Manufactures of India, Specially Compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition, 1888 By Trailokyanātha Mukhopādhyāẏa (https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Art_manufactures_of_India/C3QTAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0)

A Hand-book of Indian Products, Art manufactures and Raw Materials (https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/A_Hand_book_of_Indian_Products_Art_manuf/ubUUAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0)

______________________________________________________________

If you find value in my work, I hope you consider becoming a patron through Patreon. Hindu Aesthetic requires a lot of time and effort and your support would mean that I can continue bringing you the highest quality content. Link to my Patreon: